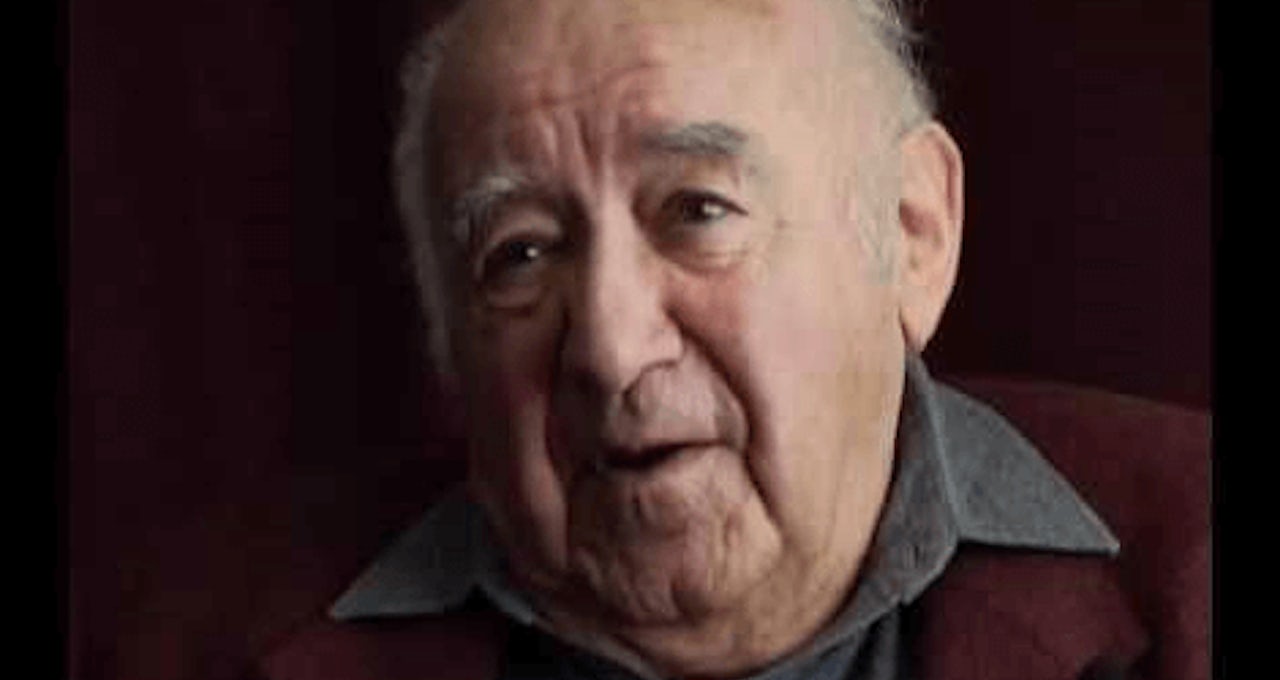

Arnold Erlanger was born in 1916 in Ichenhausen, Germany, the son of a butcher who had served in World War I. At the age of 13, Arnold found work in a factory when his parents could no longer afford to send him to school. Then, in 1935, the Nazis enacted the Nuremberg laws. His sister lost her job and the family was prohibited from engaging in social, athletic, or cultural organization.

After Kristallnacht, Arnold was rounded up with 30,000 other men and sent to the Buchenwald concentration camp. He was released soon thereafter, on condition that he leave Germany within three months. Erlanger fled the country and reached the Netherlands in February 1939, where he worked on a farm and as a blacksmith. By the middle of 1940, the Netherlands had fallen to the Nazis after just one day of bombing by the Luftwaffe.

“I have the number tattooed on my arm, in every camp we had a number we were not human beings anymore. Only in Auschwitz you had it tattooed on your arm. In the other concentration camps, you had it on your uniform or a board hanging around your neck.”

Erlanger was soon arrested and interned at various concentration camps. His first destination was Ommen Labour Cap, where he was forced to entertain the German officers and endure abuse. His next stop on the horrible journey was to Buna-Monowitz, a sub-camp of Auschwitz, where he worked in the fields and as a welder. He was later sent to the Flossenbürg concentration camp, where he was forced to carry out even more hard labor.

Flossenbürg was liberated in April 1945. Erlander was one of only two from his village to survive the Holocaust.

After the war, Erlanger returned to the Netherlands where he married a Jewish woman whose husband had died in the Holocaust. In total, he lost more than twenty-five aunts and uncles.

Afterwards, Erlanger left Europe for Australia where he would later write a memoir titled “Choose Life”. In it, he discussed his experiences during the Holocaust and described how one’s ability to work meant life or death for the prisoners. When he broke his right hand at the Buna-Monowitz labor camp, he kept working despite not being able to hold a tool.

Source: JHC Melbourne