As a totalitarian regime, Nazi Germany tried to incorporate its ideology – and therefore antisemitism – into every aspect of German society. The Reich Ministry for Propaganda and Public Enlightenment under Josef Goebbels controlled German cultural life, while professional organisations, youth movements and control of the workforce ensured that there were few spaces in which individuals could entirely avoid ideology. It is also important to remember that propaganda drew on established imagery, themes and tropes used to spread Jew-hatred over many centuries.

The press, directed by Goebbels’s ministry, disseminated antisemitic propaganda tailored to their audiences. Hardcore Nazis could subscribe to the vile, almost pornographic, material in Julius Streicher’s Der Sturmer, while other newspapers followed detailed guidelines on reporting or risked imprisonment in concentration camps. Radio, newsreels, theatre and music were similarly directed.

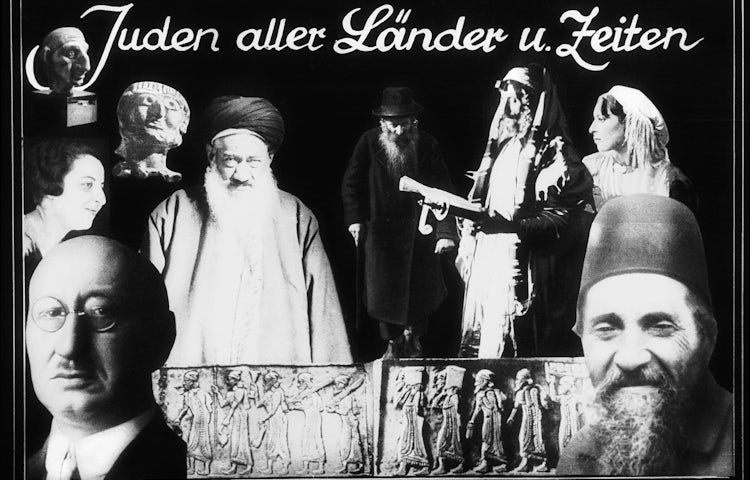

Film – the cutting edge of 1930s technology – was a key means of spreading propaganda. To support the intensification of eugenic and racial policies, “documentary” films were created to reinforce ideology: for example, films depicted the physically and mentally disabled as living lives “which were only a burden”. The 1940 film, Der ewige Jude (The Eternal Jew) used footage of the starving and degraded populations of ghettos in Warsaw and Lodz to depict “typical” scenes of Jewish life, as well as a gruesome sequence of ritual slaughter of animals. Even opponents of the regime reported the powerful impact of the film. Goebbels also favoured the development of feature films as propaganda. Films like Jud Suss or The Rothschilds (both 1940) reinforced antisemitic ideology through the their romantic or “thrilling” narratives, were intended to distract from the difficulties of wartime.

Young people were a priority for Nazi propaganda. One of the most pernicious ways in which antisemitic ideas were disseminated was through the school curriculum. Consistent with the very high degree of Nazification of the teaching profession, “Racial Science” was included in the timetable and children were taught the “characteristics” of Jews and others who did not conform to the Nazi vision of society. Problems and topics in other subjects were also given an ideological edge, with mathematics exams,for example, asking how much food was consumed by “useless eaters”. Although the constant propaganda at school followed by evening sessions of youth movements provoked some cynicism and rebellion, many young people spent all day being exposed to propaganda of one kind or another.

Attempts to make money from the propaganda drive could be of variable quality. Streicher’s book Der Giftpilz (The Poison Mushroom), for example, was widely used in schools after it was published in 1938. The same year, however, the Dresden company Günther and Co released a children’s board game, Juden Raus! (Jews Out!), in which players had to collect “Jews” and “deport” them to Mandate Palestine. Although the cheery marketing language on the box testifies to the social acceptability of antisemitism, the game drew criticism from the SS for trivialising Nazi goals and providing a target for international disapproval.